Neighbourhood Museum

30 March 2023

We talk to Olga Jaros and Piotr Gój about the new permanent exhibition at the Museum of Engineering and Technology.

Grzegorz Słącz: I’ve just had the opportunity to explore the maze that is the new Museum of Engineering and Technology… You are developing a new exhibition which will be launched very soon*. What direction does it take you in?

Olga Jaros: We frequently ask ourselves how to develop our narrative. We have created a structure of disciplines, superimposed a chronological framing, and picked out key issues. And it’s issues such as streetlights, heating and mobility that form our main narrative. The divisions between periods are somewhat vague, and the sections include Beginnings, Pre-modern City, First Industrial Revolution, Second Industrial Revolution, Towards Modernity, Post-war Modernisation, Transformations, and Epilogue. In each era we focus on the field we consider especially important.

For example, we consider electricity to be key in the second industrial revolution, and it gives us the opportunity to talk about streetlights. I like this example because we have a fantastic collection illustrating it. In the section about post-war modernisation – when Poland was gradually recovering from the Second World War – we focus on our motoring collection.

G.S.: I imagine you needed to expand your exhibition space.

Piotr Gój: We had to double it! Before the refurbishment, our museum collection was split among different buildings. The simple fact that we have combined all our spaces in the Wawrzyńca quarter means that the museum has vastly expanded its usable space and doubled the exhibition space. We have acquired additional space beneath Building D, the former narrow-gauge tram depot, and beneath the courtyard.

photo by Paweł Suder

G.S.: These are brand new spaces – have they been freshly excavated?

P.G.: There is one old cellar which has been renovated and preserved, but most of the underground space is new. The greatest difficulty was conducting safe excavations beneath the existing building. We had many investment and construction problems, but a year on we have emerged successfully and we will soon open an exhibition space of 3200 m2.

The museum presents exhibits of various sizes so theoretically it would be very easy to fill this space – however, to achieve what we wanted we needed to create this maze you mentioned. Even the quickest walkthrough takes about an hour. How do we talk about technology and engineering? It’s difficult, and we want our visitors to understand and experience what we want to show them.

G.S.: We are in Kraków, City of Kings and capital of culture, where we have Wawel Castle and impressive art collections. How does the Museum of Engineering and Technology fit into this?

O.J.: The social function played by museums like ours isn’t easy, and this doesn’t just apply to Kraków. We celebrate mundane objects – fridges, washing machines, dryers. But that’s precisely our mission: to show the public that these fridges, washing machines and dryers are as much an element of our heritage as paintings, sculptures and arts and crafts. We want to show that these objects also deserve our attention and they are worth preserving for future generations; that this technological heritage is worth protecting.

Washing machine Miele, ca. 1905, Gütersloh, Germany, producer: „Miele & Cie. photo courtesy of the Museum of Engineering and Technology

P.G.: We see grandparents with grandchildren, parents with kids. Older generations are showing youngsters items from their youth. According to studies, young people don’t know about cassette tapes – they wouldn’t know how to put them into a player or a Walkman. They’ve never even heard of a Walkman!

G.S.: Showing how technology has developed over time is an illustration of how our civilisation has developed, and with it our city.

O.J.: We’ve undergone something of an evolution – we found that talking about the development of municipal engineering alone is very limiting. It’s far more interesting to discuss engineering and technology in broader terms – after all there would be no municipal engineering without technology. We have built exhibition themes around the development of certain solutions making our individual and communal lives earlier, but really they are just an excuse to talk about the history of technology.

Changing the name of the museum was the natural result of the intellectual process we went through. Our greatest exhibition space is still the city streets – that’s where municipal engineering exists, and moving it to museum rooms or warehouse is simply impossible. We needed to find a different formula, and internal discussions led us to the conclusion that there is no municipal engineering without technology. When we talk about energy, we want to also talk about power generation in general and issues involved with it, rather than focusing just on municipal power plants.

G.S.: What’s your message for young people visiting for the first time? What do you want them to remember?

O.J.: When I think of such theoretical young visitors, I want them to leave hungry for more and planning their next visit. I have no doubt that visiting the exhibition once can be confounding: on one hand we are trying to explain energy, and on the other show a schematic diagram of a hypocaust… The beauty of our exhibits isn’t expressed in ways we usually expect from museums, such as through particular shapes or colours. The beauty of our exhibits is only truly revealed when we see how they work.

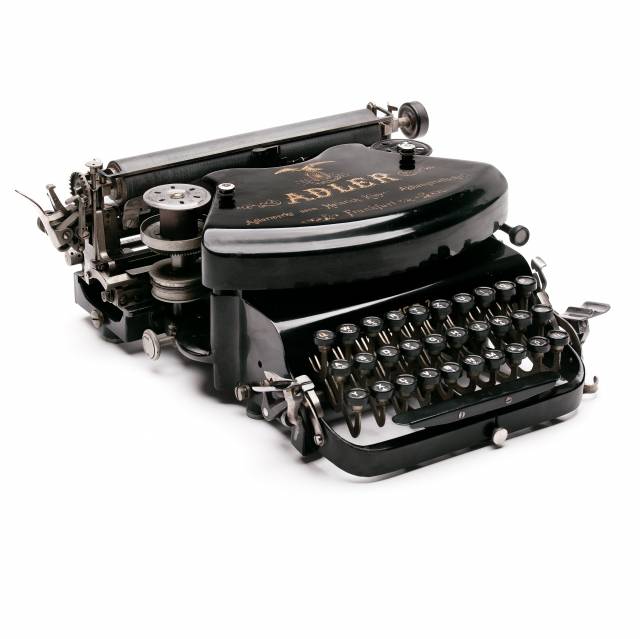

Typewriter Adler 7, ca. 1915, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, producer: Adlerwerke ject: Wellington Parker Kidder (Empire brand), photo courtesy of the Museum of Engineering and Technology

P.G.: It’s fair to say that technology develops where people live in close proximity – gas supply was originally needed to provide street lighting, and the development of good quality piping removed the need to run sewage down gutters. In reality it’s difficult to bring the whole city into a museum, and creating numerous models isn’t right, either. We show how engineering and technology develop through daily use – we are a museum which preserves the heritage of daily use. No-one imagined washing machines before running water, but eventually people wanted to wash their clothes at home. We want our visitors to become interested in these devices and their function, but I disagree that they don’t also have a beauty of their own.

O.J.: Sure, but their appearance isn’t why we choose them. We are getting growing numbers of queries from museums focusing on art and design, asking about our collections. Of course we are delighted, but design exhibitions at art museums rarely include names of engineers or constructors even though they almost always include the name of the designer responsible for the object’s appearance. For us, the construction ideas hidden behind this appearance are of the utmost importance.

P.G.: We all know that paintings must be preserved, but no-one believes us when we say that it costs around 100,000 zlotys to maintain a Fiat 125p for future generations – “surely you can get one at any car auction”. Not any more, there are hardly any left. And they genuinely require meticulous conservation.

G.S.: So the museum acts as a guardian of this technological heritage?

O.J.: Of course that’s just part of the answer; we must give a lot more than we take. As well as the exhibition we are about to launch, our other main activities are in education. It involves expanding our activities beyond museum lessons – although we will continue with those as well, of course.

The Museum of Engineering and Technology has very high attendance levels. That’s part of our answer to your earlier question about the place of a museum of technology in Kraków. People want to come here because we’re a neighbourhood museum: at the intersection of two streets in Kazimierz, with gates on Gazowa and Wawrzyńca streets, and with a large, open courtyard. I would love it if Kazimierz residents thought of us as simply neighbours; if Cracovians visited us even more frequently because they’re not afraid of coming.

G.S.: You want them to understand there are no barriers, is that right?

O.J.: Museums spend a lot of time and energy working to make sure visitors aren’t afraid of them. We have a relatively simple task. Our exhibits speak to our visitors, but their background and workings are far more complex. This is a challenge – and there is no better way of rising to it than developing a broad, thoughtful educational programme aimed at kids, schools and adults. Adults are especially important, since they transmit experiences, emotions and knowledge by sharing them with their kids or grandchildren.

P.G.: As well as our employees, we want our visitors to also act as educators. Many adults are familiar with our exhibits from their own experience, so I want them to bring their kids or grandchildren ready for what to find and to take on the role of a guide.

The potential is vast: in spite of limited access in recent years, due to renovation and expansion works, we have had no problems with attendance. Currently, only our tram depot is open, yet we are still seeing around a thousand visitors per week – even though the museum is nominally closed!

G.S.: What are your personal favourite exhibits?

P.G.: I love all complex mechanisms, from typewriters to fax machines. I’m also delighted by how objects change, and by restorations – we brought back to life a Fiat 508 and a C-Type motor-driven tram car from 1925. The museum continues to surprise me – we recently acquired a working Odra computer, the last of its kind in Poland.

C-Type motor-driven tram car, no. 260, Lilpop, Rau & Loewenstein, ca. 1925, Poland, Warsaw, photo courtesy of the Museum of Engineering and Technology

O.J.: I love all our objects, I think of them as our children. Perhaps my favourite is our steam engine which we display as part of the section covering the first industrial revolution. It is a symbolic object for us – a key in our discussions on energy and its generation, and on the technological breakthroughs which launched the modern era.

Portable engine, 1890, Czechia, producer: První prostějovská továrna na hospodářské stroje F. Wichterle, photo courtesy of the Museum of Engineering and Technology

* The exhibition The City. Technosensivity is open from 31 March 2023.

Piotr Gój

An economist and cultural manager. Director of the Museum of Engineering and Technology since January 2017. Previously he served as deputy director of the Nowa Huta Cultural Centre.

photo by Bogusław Świerzowski

Olga Jaros

A cultural manager and museum curator. She has been working with the Museum of Engineering and Technology since 2018. Member of Fundacja Kultury Paryskiej.

photo by Piotr Banasik

The interview was published in the 4/2022 issue of the “Kraków Culture” quarterly.